I’ve heard that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche once gave a teaching called, “Trust Run Wild.” I wasn’t there. I don’t know what he taught. But I was struck by the title and have had my own ideas about what such a teaching could say. Trust is a facet of our Buddha-mind, the basis for relating sanely with our world, but few people ever discover it as a way of being. It remains rare because the unexpected avenue by which we would arrive at trust is through opening to ambiguity ( and with it to vulnerability and to threat). If trust is form, then ambiguity is emptiness, and oh my friend, emptiness is form. Trust and ambiguity, trust and doubt are not mutually exclusive. Trust and all forms of sanity, individual and social, arise only when ambiguity is welcome.

In many circles, it is not fashionable to question things. It is deemed disloyal or unpatriotic. But this approach is inherently problematic. If we do not work with our doubts and questions, we will not learn or grow, we will lose the opportunity that dissonance presents, the opportunity to discover genuine congruence; the opportunity to transform our relationship to self, others, to society. In a book I found very interesting, Give Me Liberty, Naomi Wolf writes, “Over the past four decades, patriotism was often defined as uncritical support for U.S. politics… Finally patriotism was re-branded as the silencing of dissent…but all these re-brandings of patriotism would have dismayed the great Americans [our founding-fathers] who had all at times criticized U.S. military actions, U.S. policies, the establishment of any state religion, and most of all criticized those who would silence disagreeing voices and dissent.” What is that mentality that shuts down questions, questioning and divergent opinions? It is the mind of fear, of distrust and it is not only a political phenomenon. I see that mentality blocking students from genuine learning and growth. The latest American fashion of silencing dissent is not only a threat to free society, it represents a frame of mind that is problematic in our Buddhist practice. In Buddhism, the process of rigorous questioning and turning doubts into whole-hearted explorations are key elements in getting acquainted with the true meaning of the teachings.

Doubts and questions are not necessarily a sign of disloyalty. They are a crucial aspect of the process of learning in life, of the organic unfolding of intimacy in relationship, of expanding our perspective to see things in new ways on the Buddhist path. Perhaps people feel so shameful about doubts because culturally we have little capacity for respectful dialogue. Respectful and gentle speech opens the doorway to many conversations which graciously allow room for doubts. But when doubts are not brought up in the spirit of learning and curiosity, instead of doubts being the basis for genuine communication, those doubts arouse resentment and aggression. The feeling of uncertainty presented by doubts is not welcome in a mind that clings to form. So aggression is aimed towards whatever reality is not black and white enough to feel comfortable with, better to destroy it than face the breakdown of reality as we have known it. Or the aggression is aimed at oneself for not living up to some ideal of perfect faith and loyalty. Or we simply shut down and deny the doubts (until we can’t). Dualistic mind decides that if something or someone doesn’t fit into some tidy box labeled “right” or “true” then it must be wrong, burned, hanged, obliterated! Then the onslaught of name-calling, insulting, and demonizing the other ensues. There is no genuine communication in that rigid atmosphere, and so doubt mixed with bigoted-ness ends up giving doubt a bad name. But there is another way to relate to our doubts, they can be wielded as open-ended questions that open us to a genuine exploration of the path. The alternative to “right” and “true” is not necessarily wrong and false. A third alternative exists – open-end-ness, emptiness, the key principle of non-duality and why Buddhism does not lend itself easily to black and white thinking. We only encounter this reality directly if we can ask honest real questions. That’s where all the juice is.

When doubts are treated as proof that what we are doubting is fundamentally wrong and bad, they become the basis for aggression. It is neurotic to take a “guilty until proven innocent” approach. If we come to the situation with fear, tension and negative projections – that will have an effect – not just on the other person – but on ourselves, on what we will allow ourselves to see and understand. Unfortunately, we can blot out the facts of the situation and see things as we assume them to be rather than as they are. What is the alternative to guilty-until-proven-innocent? It is not blind faith. Both are extremes of confusion that avoid using awareness and intelligence. Both avoid communication and the threat that communication presents to our assumptions. Instead, a third alternative is to approach situations in an open-ended way. We are willing to let situations speak for themselves. We are willing to let situations and people communicate to us directly. We can see things as open-ended and make room for things to reveal themselves. We can inquire with the mind that does not know in advance what the answer will be.

In this case trust is not the opposite of emptiness, it is the acknowledgement of it – a willingness to step out into open space. In ordinary trust we have the idea of trusting some thing, something solid, something certain, something definite. That would lead to anxiety because everything is actually impermanent. A Vajra-trust refers to an acknowledgement of impermanence, change and emptiness, there is a stability and confidence that comes from recognizing that uncertainty and opening our heart to the world anyway. This trust is a sense of non-dual trust, its not about the other object, its about the trust in our own presence and intelligence that allows us to show up fully to life. In a way, this is similar to the trust we extend in love. We know love is risky, but we know its worth it because only what can be destroyed will be, what endures is the goodness of love itself. Goodness is worthwhile and worth whatever we end up going through to live by it.

Trust develops from questioning our own minds. As Buddhists can even be willing to examine and question our own doubts and our own mind! Using doubts non-aggressively would mean that the doubts are not just aimed externally. Instead, we question our own mind. Our own rationale, opinions and beliefs are also questioned. This way, doubt becomes the occasion to re-examine the very way of thinking that doubts arise from in the first place. Our whole mind can be up for inspection, up for exploration. The whole nature of reality can be explored. This is Buddhism. Buddhism is the tradition where we rigorously inspect reality. This explorer-attitude is the quality required of all students who wish to enter into Buddhist practice. This is what it is to operate outside of conditioned scripts, preconceptions, rigid opinions and fixed views. We can give our awareness a chance. We can breathe, sense and dialogue with our world, exploring the elements of our own mind. We can open to the radical unpredictability and vividness of perception. Openness is the basis for authentic trust. It is a simple and relaxed mind of genuine inquiry that leads us to contact the goodness and workability of our world.

Doubts don’t necessarily imply that there is something fundamentally flawed about what we are doubting. Having doubts about the Buddhist teachings is not a problem. Quite the contrary, it is a very important part of getting to know the teachings. Perhaps the wisdom we are hearing is beyond our experience; perhaps we misheard it or misunderstood it. Perhaps our preconceptions, conditioning and rigidity have blocked us from hearing the true meaning of what was being said. Perhaps we have no connection at all with what is being said, and this tidbit or even the entire path may not be for us. The only way to find out is to turn our doubts into genuine questions. Turning doubt into questions is a way of developing our intelligence, which is imperative to train in Buddhism. Buddhism is a way of living without fixed formulas, wherein we must be experienced in relying on awareness and intelligence on the spot. Awareness is reliant on having the trust necessary to communicate with our world.

Beyond Blind Obedience

Blind-obedience is not an option. It is a pale imitation of honor. Genuine loyalty is based on deep understanding. The doubtless state that vow-carrying practitioners eventually find themselves in is not some ideal starting point in the path. Buddhism doesn’t require us to start with faith, we can start from our own experience as it is. A deep trust arises organically as questions are welcomed and addressed, then doubts dissolve of their own accord. A deep trust coincides with awareness as our direct perception of what things are precludes doubt.

Trust can develop in a relationship when there is room for any question to be asked. It can also arise spontaneously as a kind of recognition of the whole nature of a situation. In that case, it is not that questions arise and we let go of them in faith. Instead, we remain without doubt because our understanding developed to that point. We had enough faith to trust mind enough to explore our doubts and this led to direct experience. However in the early stages of the path, questions appropriately arise and we must utilize them. If we don’t bring our questions into the relationship with the teacher and the teaching, then the relationship, and our understanding of the path, will never go deep enough for a mind beyond doubt to be discovered.

Going forward into uncertainty

The interesting thing about Buddhism and Vajrayana in general is that there is a stage at which our doubts and questions are already answered in their inception. We arrive at the stage of doubtlessness through a long term process and mingling our minds (doubts included) with the teaching. Through our vigorous exploration of practices and teachings, through our experience of the teacher, we may develop a certainty that any doubts that arise will also be cleared. This is just like growing trust in relationship to anything. We come to rely on steady ground by testing that ground.

Ironically, in the mind of growing trust, we can then take more risks, step out into more uncertainty. That is what trust is after all, a willingness to go forward into uncertainty, despite uncertainty, perhaps even because of uncertainty. It is an openness, a willingness. Fundamentally trust is a state of awareness, and therefore it is accessible immediately. Recognizing the qualities in a situation for what they are – we arrive as we are, open despite any risks that implies. If we waited for all the variables to be known and secure, we would never know trust. Waiting for all the variables to be known is pursuing a fantasy trust, a faux trust. Life is both known and unknown, form and emptiness, there is mystery, there is uncertainty. Trust is the mind that does not have to protect itself from impermanence, in-substantiality, insecurity or ambiguity. Our trust of the situation makes room for possibilities that only exist when there is no hesitation, no holding back. Anything can happen and we aren’t having to anticipate that in advance, so we able to be more present in the moment. With trust a tremendous freedom ensues. Wild is a good description, as our raw, deep, spicy, basic ingredients come to the surface when trust allows us to drop our self-protective games – and show up to direct experience. The edges of reality and the limits of mind and the beauty of relationship can be explored and enjoyed. We have leaped beyond our own rationale, creeping past our superstitions and fears to find the pervasive goodness that is.

Beyond Doubt and Trusting a Teacher

There is a stage in the path where there is no doubt. That is the ideal in terms of an advanced stage of practice, a dimension in which our dissonance has been exhausted organically, not by force and not by blind-faith, but by the unraveling that happens when goodness and trust in it is discovered. The explorer mindset leads us to natural confidence. We are congruent with the possibility presented to us by the teachings and even by our teachers. That can happen. We can experience congruence. Our congruence with the teachings and with our root-teacher is the basis for developing congruence with what is.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, we do take a long-term thorough investigation into the relationship with the root-teacher before we enter into Vajra commitment. Still, like any relationship, a relationship with a teacher presents us with a litany of unknowns and un-predicability. We can get to the point of being willing to step into that without an insurance policy, because we have used the explorer mindset to develop trust. Then we feel more relaxed about the uncertainties and maybe even poetic about them. Like poets, artists and lovers have felt since the beginning of time, Yogins are compelled to go forward as we are, into the situation as it is, trusting the goodness of that explosive uncertainty. We know we can always rely on or own intelligence. We know know we can always rest into authentic presence. We know we can communicate and learn and evolve situations through our authentic and gentle speech. So it is safe for us to communicate with others. The more confident we are in our own relationship with our own mind, the more relaxed we can be about relating to others. We don’t get to that stage by imitating it, pretending we are there. We get to that place by starting where we are; there is Buddha-mind in the organic pace set by our authenticity.

Perhaps we are so afraid of our doubts because they present ambiguity. Many people mistakenly think that ambiguity does not belong in religion, but ambiguity is a key to the Dzogchen view we practice. Emptiness with all its un-definability is welcome here.

I have noticed that new students, especially in the connection with a teacher, look for some formulaic approach, some way to finally feel comfortable and relax by completing all ambiguity forever. This wish is brought to every relationship but is markedly noticeable in the Vajra relationship. If our teacher is a Buddhist they have devoted their whole life to relaxing in uncertainty, so there is no way of getting around that quality in relationship to them. No formulaic approach will replace that. But the formula is not available in there because it is not available in reality, or in any of our relationships. But in the Vajra world there is no pretense otherwise. We simple have to work things out together, one interaction at a time, live on the spot, with no rehearsal, just open authentic presence. Lack of a safe formula for relating does not doom us to endless tortuous encounters with our root-teacher, even if it does promise continual uncertainty. If we were to relax and settle into the ambiguity, then we find the simple exhilaration of being in the moment. The ambiguity turns out to be what we are. No fixed formulas are there to guarantee anything, but the guarantee is not needed. There is ample goodness in the situation as it is, if only we can relax and be present enough to connect with it. Even awkwardness has a goodness we can trust.

Genuine Questions Are A Sign of Trust

Doubts that are un-addressed do not just disappear. Doubts can be wielded in a way that is neurotic if we hold on to them but never voice them. We can fear them, hide them and harbor them secretly and then they become poisonous. They rot and ferment, proliferating to become barriers to genuine understanding, growing from small infections to metastasized cancers that prevent us from having genuine intimacy with each other, with the teaching. But doubts can also be brought up with the spirit of genuine inquiry and then they become opportunities for clarity. I have noticed that many people seem to fear their doubts and questions as if they are some kind of sign of lack of devotion. On the contrary – our questions are a sign of trusting our situation enough to explore it. We trust our connection with something or someone enough to test it, knowing it may actually survive the test, trusting that there is a goodness that could withstand our testing. Such trust is the unfolding of our Buddha-mind, a discovery that relies on us trusting enough to experience what we are. We can reason and ask questions and make inquiries and investigate the practices because our own confusion is a good basis to begin with. It is fertile and has surprising possibilities in it. It turns out to be wisdom, albeit wisdom in confusion’s clothing, awaiting our contact with it’s naked quality. Doubt is not the barrier to trust and devotion – it an aspect of its unfolding.

Going Haywire

Trust is a willingness to communicate with our experience. Communicating directly, kindly and fearlessly with another is only possibly we have established such a communication with our own mind. If we fail to communicate directly with our own minds, then we will have no capacity to communicate with our world. This is why meditation practice is important at every stage of the path. If we fail to communicate directly with our world we will know it’s goodness less and less, we will understand it less and less. Then we will have cause for paranoia and skepticism, because our irritation, dissatisfaction and suffering comes out of nowhere. Misunderstanding our own mind, we misunderstand our world and then miss the life cycle of every dynamic we are in. Then we are surprised when unfortunate circumstances arise, feeling helpless and un-empowered by our own misperception, we fall into the mind of fear and blame. Distrust as a habitual view pervades. Strategies of self-protection ensue and our lives can get complicated and ugly.

When they are not turned into genuine questions and learning, doubts can go haywire into paranoia and cynical skepticism. We must have some basis of trust to start from, some straightforwardness or there will be no communication with our world. Our constant agenda of managing our self-image will have to be let go of so that our communications can be more direct. Our habit of projecting our own un-trustworthy-ness onto others will have to be let go of if we are going to hear what others are actually saying.

For example, there is some sad assumption that wisdom, goodness, sincere people, enlightenment, realization and great teachers could not exist except as facades. That’s what happens to us when we are alienated from our goodness and only operate from manipulative, contrived, self-serving agendas. From that state, it is easy to assume others are doing the same. This is why meditation is so important. We have to get to know our innocence or we will not be able to communicate with the goodness in the world or believe that it is possible in others. The more we experience our own goodness the more we feel we can trust others’ goodness, we can see there is a whole world of sincerity, innocence and beauty out there. We can take a straightforward approach, which is the only sane way to be. Trust of our own goodness is where all trust begins.

Walking down a steep hillside

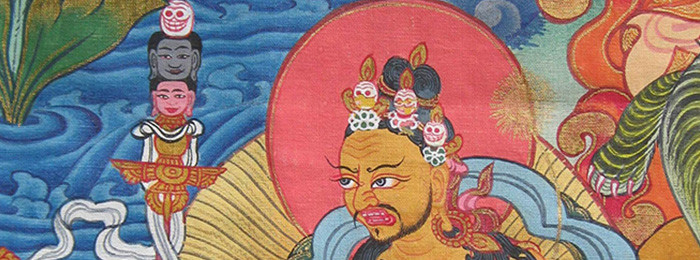

In the Gesar teachings, Ngak’chang Rinpoche once told a story of how to walk down a steep, crumbling, rocky hillside. I heard him say that it is a completely unstable situation, so if we try to find stable secure footing there, we will have a hard time because we are looking for a security that doesn’t exist. But if we relate to it as the unstable situation it is and ski briskly down the hill, staying in motion – then the instability is not a problem. I took this as an instruction on how to live. It also seems to be a vivid illustration of why people often feel so alienated from trust as a way of being. When we are waiting for a situation that is secure, stable, solid and definite, we will never find anything to trust. But instead, if like the person running down the hill in Rinpoche’s story, we work with our situation as it is, ambiguity, doubt, impermanence and all, we will discover it is quite workable. We find a way to be steady in instability.

Buddhism is a method for investigating reality. It does not give us a tidy view of the world that explains away all threats, and promises a happy ending. Quite the contrary, it introduces us further to groundless ground. It urges us to step beyond belief into the open sky of direct experience. It urges us to explore the texture and nuance of what we are, beyond concepts, assumptions and beliefs, to step into ambiguity, to make room for questions. If we do this, we find insecurity is no problem in and of itself, it is even trustworthy. Doubt in and of itself is no problem, it is an aspect of our intelligence. Things are only problematic if we look to them for a security that is not there. We can fabricate that security by demonizing what we doubt, or demonizing ourselves for doubting, that turns an ambiguous situation into a safer, defined one. Or we can explore our ambiguity, we can use our doubts as the occasion to venture into the unknown, into the endless horizons beyond our understanding. This is the great adventure. The virgin frontiers left to explore are no longer on land, they are in mind. We are the brave pioneers who can traverse it so long as we remain open to the unexpected. There is goodness there. There is Buddha-mind there and our trust can run wild in it.