We often think of heroism as something that occurs in moments of grave overt crisis, as if the edge of life and death are met only in moments of high drama, quite set apart from daily life. But in Buddhism, warriorship also points to something more pervasive, a way of being that could be found in our very own little moments of time whenever we allow ourselves to enter the challenge of every day experience without retreating, without shutting down, without holding back.

There is some power of warriorship that we can find as an every day facet of our Buddha-mind. It is there in our sense of not giving up on goodness and kindness, it is there in the sense of courage required to be on the spot in the pouring rain and blazing sun of life experiences. We don’t often allow ourselves to express it. Perhaps that’s part of why the movies about heroes sell so well – while we watch them, we get to taste the most under-utilized aspect of what we ourselves are. But intuitively we are deeply connected to heroic energy.

Having Heart

Life and death are always meeting in the present moment and when we rise to perceive that meeting in an unflinching way, we find our warrior’s heart, our Buddha-mind. We are always facing the constancy of death as the ultimate threat, it appears as vulnerability and unpredictability and in many other forms. We launch into neurotic cycles as an attempt to avoid this constant threat of emptiness. There seems to be a phobia about our vulnerability, about the empty nature of existence. It is a phobia heightened and developed by avoiding it. Every time we avoid insecurity, change, the gap, the groundlessness, the reference-less-ness, we get more disassociated from what our empty nature actually is. We get less experienced at being in it, so the prospect of remaining with it seems more and more remote. We imagine its chaos to be some kind of enemy; we see its groundlessness to be some kind of error, when it is really the freshness of our life. Our vulnerability can be a source of ultimate strength and is the only genuine source of joy. It is the occasion for discovering warrior-heart-Buddha-mind, a phenomenon available to us when we dare to be what we actually are.

When we dare to contact the raw tenderness of our life, our warrior-heart-Buddha-mind is discovered. Our warrior’s heart is tender, pink, raw and fleshy. It is completely vulnerable. That we do not protect it is its strength. We are willing to hurt, willing to bleed, willing to spill our own guts and this is the unexpected brilliance of the warrior – s/he is willing to die. This does not necessarily refer to physical death. Physical death can be easier than the death of self-preservation, since we could die physically without yet facing the death of self. Pictures falling away before our very eyes; identities peeling back; reference points lost; being exposed as the brilliant, foolish weirdoes we all really are; the death of our self-preservation is not always pleasant. To let go of our rigid compulsion of self-protection, self-maintenance, self-defending and Self-establishing is the ultimate risk, requiring the immense bravery because it thrusts us into uncertainty, ambiguity, vulnerability; this is what is meant by the term “emptiness,” the open-ended fact of life that most people deny. To face it requires the everyday-warriorship of ordinary people who are willing to venture beyond the fortress of self into the vast wilderness of being beyond definition.

“Now is the time to reveal your faults, lay bare your inadequacies.

Expose your secret self and take courage.”

-Padmasambhava to Yeshe Tsogyal, Sky Dancer

We have thought of warriors as people who are experts in self-protection and self-defense. There is another kind warrior that few people ever encounter, warriors as experts in self-liberation.

When we are preoccupied with self-protection, we are limited in our capacity to communicate with the situation at hand, to listen or respond. We are incapable of caring for others properly or addressing the situation appropriately. Self-maintenance is too cumbersome to allow it. But to step outside of Self-protection puts us in an interesting position. We have nothing to lose. Now we can truly get into things without holding back. Now we can be genuine. Beyond Self-protection we no longer have to fight off our own vulnerability. Only then can we find authentic communication, compassion and respect for others. The ultimate sign of genuine warriorship becomes available to us, kindness.

Kindness is one of the most powerful forces on earth. Kindness is one power that is so often underestimated. It has so many forms and can be wielded so precisely. Kindness as a facet of warriorship is rarely told about in stories, movies and comic books. Perhaps it is because so few people have experimented with it enough to appreciate how much wisdom and mastery it takes, how heroic it truly is. Whatever grave situations we face in life that may demand the more conventional expression of warriorship, the greatness of those moments is rarely isolated. Its true on one hand, that the heroism we express in crisis and turning points is causeless, it is accessing something that was always in us. Yet paradoxically, it is also grown from the ground every-day-warriorship. All our little moments in time are an important training ground, a basis for practicing our connection with warrior-heart-Buddha-mind. There are many moments in a life, that we will need to rely on the fruit of all such practice.

The Sharp Edge of Life

Buddhism doesn’t shield us from the sharp edge of life. This is what I personally love about it. I have heard a tale of a woman approaching the Buddha when her young child had died. She heard that Buddha was a great Master and so came asking him to revive her child. He agreed to do so when she could bring back a sesame seed from a home that had not been visited by death. She searched every house she could find. In the end, she returned with no sesame seed. Every house had been visited by death. Instead of performing a supernatural miracle, he introduced her to the nature of things as they are. Padmasambhava was requested to save a young girl in a similar way. She had just died and at a very young age. He also agreed, yes, he would revive her. And he did revive her, but only long enough to give her transmission of the Dakini’s Heart-Essence teaching. Then she returned to her death. It was a shock to everyone, not what was expected. He did not save her from death, yet he did save her from Samsara. The two Buddhas in this story had something even more powerful to offer than life without death; they offered awareness. Awareness is the mind of non-confusion, the mind of the Buddha, the mind in which there is room for life to be as it is, sharp-edge and all. Though we often think we can’t take the intensities of life, we can. Awareness is our nature; warrior-heart-Buddha-mind is what we are made of.

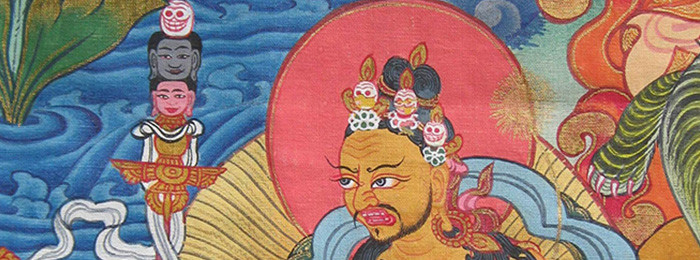

LICKING HONEY ON A RAZOR BLADE

There is a quality of fearlessness in enlightenment, not regarding

the world as an enemy, not feeling that the world is going to attack

us if we do not take care of ourselves. Instead, there is tremendous

delight in exploring the razor’s edge, like a child who happens to

pick up a razor blade with honey on it. It starts to lick it; it

encounters the sweet taste and the blood dripping off its tongue at

the same time. Simultaneous pain and pleasure are worth exploring,

from the point of view of the sanity of crazy wisdom. This natural

inquisitiveness is the youthful-prince quality of Padmasambhava, a

great teacher who helped bring Buddhism to Tibet. It is the epitome

of noncaring but at the same time caring so very much — being eager

to learn and eager to explore.

– Trungpa Rinpoche, Crazy Wisdom

We could easily shut down, close off or lock all our doors and windows, rather than love again or dare to communicate in difficult times. Our capacity to feel is so powerful that it can seem threatening. We can never quite make it as secure as we imagine it could be. We fall in love and are tremendously happy, but also there is a pervasive sense of tenderness. The more committed we get, the more vulnerable we are. We can’t seem to chase the vastness away. And we don’t need to. We can dare to live in it. We can dare to feel good anyway. Life of itself, is actually good and worthwhile as it is, sharp-edge and all. Warrior-heart-Buddha-mind; we can bear it.

Openness is the quality of every-day-warriorship. There is really no reason to be open – beyond the goodness of experiencing the openness itself. Relying on any reason beyond that leads to dissatisfaction. Having no reason and being open anyway is possible because of our Buddha-nature. It shines its light without cause. It is self-existent goodness beyond all causes and conditions.

Communicating or expressing creativity requires an every-day-warriorship-courage. It is so vulnerable. It is bold to create despite the wave of critics and naysayers, the avalanche of “shoulds” and comparisons. The haters are always out there hatin’ so loudly. To express anyway takes guts. Just to create, just to communicate is somehow so innocent and so bold. It requires a tolerance for allowing our art of Self to be seen in ways we may not like. But in our warrior-heart, we have room to do that. There we can find we are living for something more important than other people’s approval or understanding. We are expressing things for goodness sake and that is enough. Our art can be set free into the world as it is. It (and we) can be like a mirror accommodating whatever projections are set upon it without losing anything, without falling into confusion. That is a heroism that is rarely noted, but makes the difference between a life of suffering and a life of satisfaction.

Sometimes certain people seem to mistake Buddhism as some kind of somber, unfeeling path or a path with some kind of grim outlook on life. It is true that Tantric Buddhism is not a teaching that leads to an ever-lasting-happy-land, where enlightenment is equated with blissful sunshine and rainbows on blue and pink frosting clouds of holy heavenly holiday. Instead it offers something better than that – reality is always more satisfying than fantasy. Pain and sorrow do continue as a fact of life, no matter how much we realize Buddhist wisdom.

Even highly realized beings feel pain when they stub their toe or get a splinter. We could remember Yeshe Tsogyal when her teacher died. She was a MahaSiddha, the Tantric Buddha. She was the ultimate example of true dharma practice. When her teacher died, she threw herself at the ground, tearing her hair, scratching her face, rolling over and over like a baby, weeping and crying out in agony at the death of her teacher. That image blows apart any fantasy that enlightenment is some cold unfeeling state.

The teacher of one of the greatest yogi heroes of Tibet was named Marpa Lotsawa. He was remembered for his fierceness and tough love. We could also remember Marpa crying at his son’s funeral. How could he not? There is tremendous wisdom in our sorrow and pain. We should not think Buddhism or enlightenment is some situation without that. It is why we came built with warrior-heart in the first place. Buddhism does not promise us refuge from pain and sorrow. It promises refuge from suffering and dissatisfaction.

Suffering is Optional, Pain Is Not

What is the difference between suffering and pain? Pain is what we feel as the axe is chopping off our hand. The suffering is the tangled psychological web that we add on in addition to the pain. Suffering could be full of blame and self-referencing where we decide what this “means” about us, about life, about others, and then get caught up in a maze of anger, clinging and depression. The pain is what anyone would feel when going through the break-up, death or loss. The suffering is all the subjective convolution added to the pain, as we attempt to define the situation, grasp, protect our territory and play out conditioned scripts.

The pain, nothing can protect us from. Certainly, if there were a way, we would have found it by now. Decades, even lifetimes of our Selves and everyone we know attempting to avoid pain have proved to any adult how impossible it is to completely protect ourselves from pain. Our vulnerability is an in-erasable fact of our lives. The suffering however, has a cause, which if removed, enables the suffering, confusion and dissatisfaction (dukha) to dissolve on the spot. But to launch an investigation into this possibility requires courage, the boldness to step out of our cocoons into the brisk winds of living and loving so that we can experiment with approaching our world without armor. We must go forward without any guarantees, without any certainty, and that is also our power. A sense of warriorship is elicited and with it comes the unique joy that all heroes know intimately – the joy of goodness for it’s own sake.

“Now is the time to employ both joy and pain as the path.

Turn whatever suffering arises into the path

and be less desirous of an easy life…”

-Padmasambhava’s advice to Yeshe Tsogyal, Sky Dancer

Buddhism is a Path of Joy

In light of all this, because of the openness to pain, Buddhism is also a path of joy. Conspicuously, that’s not how Buddhism is thought of in popular culture. It’s just too easy to assume that the grim state of dissatisfaction is all that there is to life. It’s interesting how I often hear people remember only one thing about Buddhism, the teaching that “people live lives permeated by dissatisfaction (dukha).” This is most often phrased as “All of life is suffering.” It seems to be the easiest part of Buddhism for non-Buddhists to remember. What is more difficult to grapple with is that Buddha went on to complete that statement by saying that we don’t have to live that way. Satisfaction and goodness are our intrinsic nature and we do not have to live lives of suffering, dissatisfaction and confusion. Instead we can wake up and live in wisdom and goodness. All of the Buddhist teachings and traditions are filled with many methods to do so. It may be hard to believe. But belief is not what is required, only a willingness to experiment, to apply the methods and see what happens.

If enlightenment were either a solid state of peaceful bliss, or some wise emotion-less-ness, then the path would be much easier. We wouldn’t have to pay attention; we could just go on autopilot. We would know what to prepare for. Instead, we have the capacity for the full spectrum of joy and sorrow at any and all times. Instead we are faced with the delicate and precious moment juxtaposed against all time, all possibilities and all emptiness. It is excruciating. It is delightful. It is what it is to be awake and alive. It is why we come with warrior-heart-Buddha-mind; we are fit to fully experience. The Buddhist methods empower us with that realization over and over again. Even if we have lost touch with it, through the methods, we can find it again and again.

To experience goodness and be kind in our daily life is an act of heroism that is underestimated until we attempt it. It sounds so simple. Yet the fog of cultural negativity is so pervasive; it would be easier to fall into being mean or depressed. The insanity of Samsara can seem to be so sticky; it would be easier to remain in it. Even in Buddhism, (or whatever we consider our haven), there is abundant ugliness available. The mediocrity and disassociation that is considered “normal” in relationships would allow our un-kindness to go almost unquestioned. In any moment, the intoxicating tidal wave of our own conditioned scripts can seem so compelling; it is tempting to go along with that momentum. Add to all this, the fact of death, the vulnerability of life, the unavoidable risk of pain, and the sting of seeing how much suffering we have added to all this through our own ignorance – whew!!! The moment requires spiritual adulthood of heroic magnitude. It requires an unflinching awareness; warrior-heart-Buddha-mind. To dare in such a precarious situation as we are in, to remain open, to express kindness, to connect with our own and other’s goodness, is a heroic gesture. There are times when it may seem like remaining kind and vulnerable requires much more from us than mere physical death would require, but we can be kind and open anyway. Such are the moments where the essence of warriorship is realized. These moments may not become legends, but that only adds to their greatness. Rarely if ever recognized, never memorialized, perhaps no one ever even noticed – but we did it – we opened when we might not have – we have broken open to our tender, wild, vast Buddha-mind.

There is a simple and total contentment that can only be found in the moments where we accept the razor’s edge. It is innocence. It is satisfaction. It is so bare that it is heart breaking, but the heart has broken open instead of apart. It is joyous. Without protection from the razor’s edge of life, we do not sulk and whimper around, quite the contrary. If we are not preoccupied with avoiding pain, we can relax and enjoy our lives, loves and the momentary delights that color them. When pain is accepted as a possible consequence, we can continue doing the things that are worthwhile for their own sake, regardless of the outcome. Authentic joy is discovered when self-protection is abandoned.

Should Buddhists Really Be So Happy?

People often ask me why my sangha is so playful, and spends so much time being celebratory. Should Buddhists really be so happy? By world standards Americans live relatively privileged lives, yet they undergo tremendous psychological suffering. In our own community, together we have faced and continue to face our own intensities. These have included chronic illness, cancer, having our houses burned down, loss of a child, all the poisons of the mind, the ups and downs of poverty and wealth, being mugged, being robbed, being irritated and the all pervasive embarrassment of ego. We have faced and continue to face divorce, breakups, drug addiction, rape, histories of violence and abuse, the sudden deaths or suicide of our dearest loved ones. We are all living together in this strained economy. We were hosted at a farm recently where the owner told us that they had to watch the livestock because people were now stealing their farm animals for food because the economy had become so difficult. We are all also living together in this time of strange and ugly politics, our country tortures people legally, it has violently invaded another country, we are feeling the severity of the impacts of an ever increasing environmental crisis and more and worse… all experienced so personally… how can the intensity of life really be described? We are not strangers to pain and sorrow. Yet we still love and we still play because the Dharma has given us a method to remain open and to keep showing up to life’s joy and sorrow. It’s the undeniable essence of our tradition – we can dare to enjoy our lives and appreciate what we do have, which is above all else, the Dharma: a total communication with the goodness and wisdom of existence.

Even if the three realms appear or are destroyed,

there is no fear. There is only unceasing clarity of awareness.

May all beings awaken to great vast open space.

– Kuntunzangpo’s prayer

It is not that life is always easy with the dharma, at times it really hurts. Yet through the path, we can encounter our capability to experience life as it is. Fundamentally, as raw, intense and dramatic as it can be, it is still good. In us is warrior-heart-Buddha-mind, the capacity to bear the full intensity of our situation. It is the capacity to die to fantasies and discover reality as our very nature. We are not celebrating because we are necessarily in some ideal situation. It is not because we have been or will be liked, “successful,” pleasant, safe or secure. We have these waves of celebration because, at times, we live with a particular kind of exhilaration. It is the first-hand experience of what is usually gleaned second-hand when listening to ancient stories of martial-artists and great warrior-heroes. That is why we celebrate. In our humble way, we are enjoying that. We celebrate because we are personally enjoying the untold greatest heroic drama of all time. It is a story of every-day-warriorship that most people don’t acknowledge or even realize the magnitude of. It is the story of a world where life and death, samsara and nirvana, Self and no-self, pleasure and pain, joy and sorrow all come face to face in one unrelenting moment. It is a story of ordinary, every-day warriors daring to be awake and kind, creative and loving as they possibly can, just because they can be.

By Pema Khandro Rinpoche